| Jeff Ochs |

Twin Cities practitioners of social enterprise, led by the local chapter of the Social Enterprise Alliance, have started unifying around a simple definition of the term for use in the local ecosystem.

The ivory tower debate aside, here, in our region, those on the ground now agree that a social enterprise is “an organization that sells products or services in order to achieve its social purpose.”

Let’s unpack that a bit. In short, to count as a social enterprise, an organization must pass two tests.

First, a social enterprise must officially have a social purpose. The most obvious type of organization that meets this first test is a nonprofit corporation that has received tax-exempt status from the IRS.

But other corporate forms can voluntarily declare a legally binding social purpose as well; LLCs, co-ops, and business corporations can write a social purpose into their Articles of Incorporation, compel directors to consider that purpose in all of their decisions, and require regular reporting on results.

Admittedly, it is currently challenging to form, differentiate, and evaluate social enterprises in the business world, but the arrival of the Public Benefit Corporation form in Minnesota this month changes that.

The second test that all social enterprises must pass is selling products or services. The most obvious type of organization that meets this test is a business. But some nonprofit corporations also have substantial earned revenue streams that support their social missions.

Stepping back, it is interesting to note that while all tax-exempt nonprofits meet the “social purpose” test, many do not meet the “sell products or services” test. Conversely, while all businesses meet the “sell products or services” test, many do not meet the “social purpose” test.

Since a social enterprise must meet both of these tests, it is helpful to think of social enterprise as inhabiting the intersection of “organizations with a social purpose” and “organizations that sell things.”

One of the reasons that the concept of “social enterprise” has been so elusive for so long is that it includes some (but not all) organizations in both the nonprofit and business sectors.

Social Enterprise Alliance-Twin Cities is introducing new language into the local ecosystem to help better separate these subgroups.

“Commercial nonprofits,” the phrase now used to describe a nonprofit social enterprise, earn a substantial portion of their annual revenue from the sale of products or services, while “contribution nonprofits” receive most of their revenue through donations, grants, or endowments.

“Social businesses,” the phrase now used to describe a “for-profit” social enterprise, have a legally binding social purpose that they report against regularly, while “traditional businesses” do not. These four categories and their relationship with the “social enterprise” label can be visualized in the following diagram:

Advocates of social enterprise are not implying that traditional businesses do not deliver social value. On the contrary, we celebrate that pursuing profit can and often does yield significant positive social value as a fortunate byproduct, and we point to this as evidence that the intentional pursuit of social impact and financial returns can go hand-in-hand, as they do in social businesses.

As Brad Brown and I discuss at length in our December 2013 white paper Present at the Creation, social enterprises only make sense if we challenge the traditional belief that an organization must choose either to make money or a social impact.

Instead we must recognize that every entity, regardless of corporate form, actually has both a financial value proposition and a social value proposition. Then we need to evaluate financial and social returns separately rather than assuming that profit and impact are always inversely proportional.

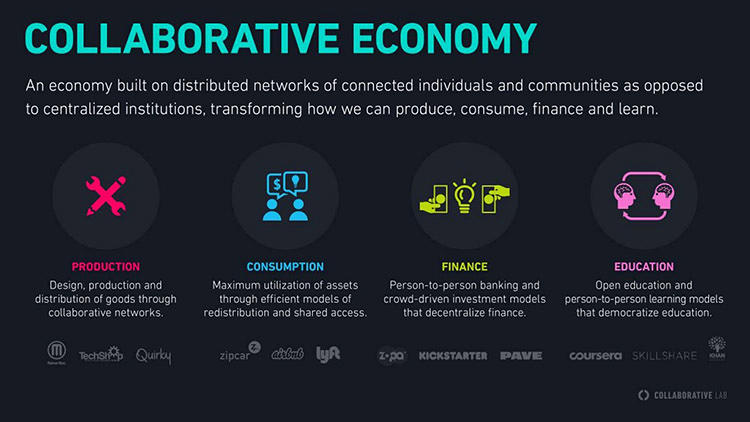

One of the greatest assets of the social enterprise movement is the tremendous variety of social enterprise models that proudly claim the label. But this diversity can also lead to confusion. Over time, local practitioners have agreed that nearly every social enterprise employs one or more of the following models: Social by sharing, by selling, and by sourcing.

Social by sharing

Some enterprises are social because they exist to share a significant amount of profit or product with other charitable organizations or causes. Examples of this type of social enterprise include:

- Finnegans, which donates 100% of its profits from selling beer to combat local hunger.

- Latitude, which donates 50% of its profits from marketing work to empower those in extreme poverty.

- Toms Shoes, which donates one pair of shoes to someone in need for each pair purchased.

Social by selling

Some enterprises are social because of what they sell or to whom they sell. In the first case, the product or service itself, when used by customers, results in a unique and compelling social (not just private) value. In the second case, a company may sell a conventional good but to a population that currently is not served by the market. Examples include:

Some enterprises are social because of what they sell or to whom they sell. In the first case, the product or service itself, when used by customers, results in a unique and compelling social (not just private) value. In the second case, a company may sell a conventional good but to a population that currently is not served by the market. Examples include:

- Revolution Foods, which sells extraordinarily fresh, healthy meals to school cafeterias in order to combat obesity and improve child health.

- thedatabank, which sells software and IT services to nonprofit organizations, which traditionally are underserved by the technology industry because they have lower purchasing power.

Social by sourcing

Some enterprises are social because of how they make their products or services. Common ways for ventures to source socially include using new environmentally friendly processes, employing vulnerable populations, locating in a certain warehouse or neighborhood, using minority-owned suppliers, and using sustainable materials. Some examples include:

Some enterprises are social because of how they make their products or services. Common ways for ventures to source socially include using new environmentally friendly processes, employing vulnerable populations, locating in a certain warehouse or neighborhood, using minority-owned suppliers, and using sustainable materials. Some examples include:

- Ten Thousand Villages, which sells products that are sourced from individual artisans from the developing world, using all natural and environmentally sustainable materials.

- Cookie Cart, which sells cookies to employ and provide job training to at-risk teenagers.

- Calera, which sells bricks and concrete made exclusively from carbon recaptured from power plant smoke stacks

In order for social

enterprises to thrive, advocates need to dispel the myth that there is

no consensus about what social enterprises are nor any tools to help

make sense of the sector’s diversity.

By repeating the same, simple definition (“an organization that sells products or services in order to achieve its social purpose”), using consistent language (“commercial nonprofits” and “social businesses”), and employing new frameworks (social by sharing, selling, and sourcing), local practitioners are not only positioning Minnesota as a leader in the international social enterprise movement, they are defining it.

Bio

Jeff Ochs runs social enterprise Cornerstone Stories and serves on the board of the Social Enterprise Alliance-Twin Cities. He played a leadership role in drafting and advocating for the Minnesota Public Benefit Corporation Act, which went into effect this month.

Connect

Address

By repeating the same, simple definition (“an organization that sells products or services in order to achieve its social purpose”), using consistent language (“commercial nonprofits” and “social businesses”), and employing new frameworks (social by sharing, selling, and sourcing), local practitioners are not only positioning Minnesota as a leader in the international social enterprise movement, they are defining it.

Bio

Jeff Ochs runs social enterprise Cornerstone Stories and serves on the board of the Social Enterprise Alliance-Twin Cities. He played a leadership role in drafting and advocating for the Minnesota Public Benefit Corporation Act, which went into effect this month.

Connect

Address

jeff@cornerstonestories.com

Website

These sentiments echo what the independent research organization Envisioning Technology predicted with their recent infographic,

These sentiments echo what the independent research organization Envisioning Technology predicted with their recent infographic,