Urban nature has a critical role to play in the future liveability of cities. An emerging body of research reveals that bringing nature back into our cities can deliver a truly impressive array of benefits, ranging from health and well-being to climate change adaptation and mitigation. Aside from benefits for people, cities are often hotspots for threatened species and are justifiable locations for serious investment in nature conservation for its own sake.

Australian cities are home to, on average, three times as many threatened species per unit area as rural environments. Yet this also means urbanisation remains one of the most destructive processes for biodiversity.

Read more: Higher-density cities need greening to stay healthy and liveable

Despite government commitments to green urban areas, vegetation cover in cities continues to decline. A recent report found that greening efforts of most of our metropolitan local governments are actually going backwards.

Current urban planning approaches typically consider biodiversity a constraint – a “problem” to be dealt with. At best, biodiversity in urban areas is “offset”, often far from the site of impact.

This is a poor solution because it fails to provide nature in the places where people can benefit most from interacting with it. It also delivers questionable ecological outcomes.

Read more: EcoCheck: Victoria's flower-strewn western plains could be swamped by development

Building nature into the urban fabric

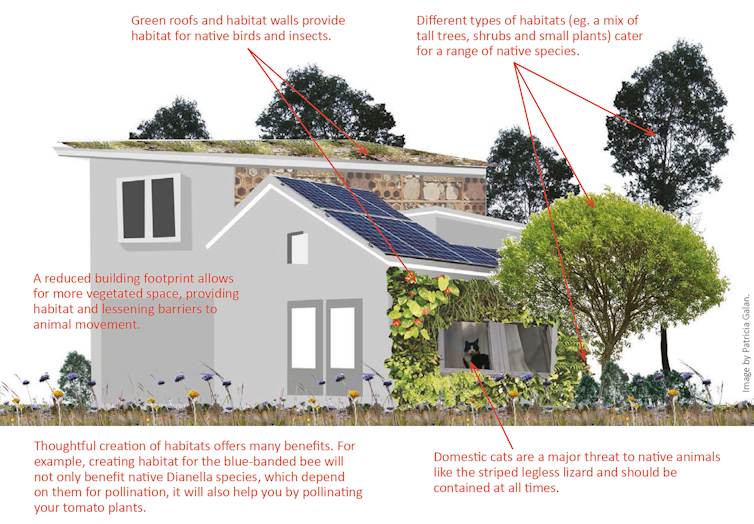

A new approach to urban design is needed. This would treat biodiversity as an opportunity and a valued resource to be preserved and maximised at all stages of planning and design.In contrast to traditional approaches to conserving urban biodiversity, biodiversity-sensitive urban design (BSUD) aims to create urban environments that make a positive onsite contribution to biodiversity. This involves careful planning and innovative design and architecture. BSUD seeks to build nature into the urban fabric by linking urban planning and design to the basic needs and survival of native plants and animals.

BSUD draws on ecological theory and understanding to apply five simple principles to urban design:

- protect and create habitat

- help species disperse

- minimise anthropogenic threats

- promote ecological processes

- encourage positive human-nature interactions.

BSUD progresses in a series of steps (see Figure 1), that urban planners and developers can use to achieve a net positive outcome for biodiversity from any development.

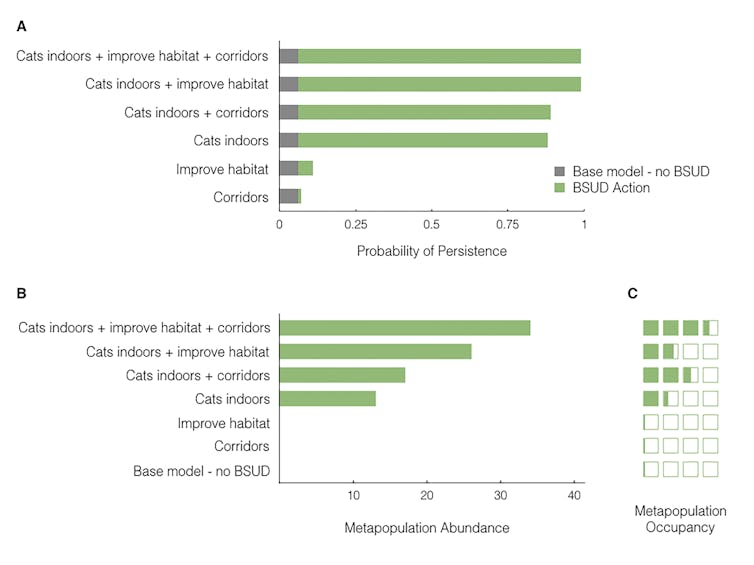

BSUD encourages biodiversity goals to be set early in the planning process, alongside social and economic targets, before stepping users through a transparent process for achieving those goals. By explicitly stating biodiversity goals (eg. enhancing the survival of species X) and how they will be measured (eg. probability of persistence), BSUD enables decision makers to make transparent decisions about alternative, testable urban designs, justified by sound science.

For example, in a hypothetical development example in western Melbourne, we were able to demonstrate that cat containment regulations were irreplaceable when designing an urban environment that would ensure the persistence of the nationally threatened striped legless lizard (Figure 3).

What does a BSUD city look, feel and sound like?

Biodiversity sensitive urban design represents a fundamentally different approach to conserving urban biodiversity. This is because it seeks to incorporate biodiversity into the built form, rather than restricting it to fragmented remnant habitats. In this way, it can deliver biodiversity benefits in environments not traditionally considered to be of ecological value.It will also deliver significant co-benefits for cities and their residents. Two-thirds of Australians now live in our capital cities. BSUD can add value to the remarkable range of benefits urban greening provides and help to deliver greener, cleaner and cooler cities, in which residents live longer and are less stressed and more productive.

Read more: Why a walk in the woods really does help your body and your soul

BSUD promotes human-nature interactions and nature stewardship among city residents. It does this through human-scale urban design such as mid-rise, courtyard-focused buildings and wide boulevard streetscapes. When compared to high-rise apartments or urban sprawl, this scale of development has been shown to deliver better liveability outcomes such as active, walkable streetscapes.

By recognising and enhancing Australia’s unique biodiversity and enriching residents’ experiences with nature, we think BSUD will be important for creating a sense of place and care for Australia’s cities. BSUD can also connect urban residents with Indigenous history and culture by engaging Indigenous Australians in the planning, design, implementation and governance of urban renaturing.

Read more: Why ‘green cities’ need to become a deeply lived experience

What needs to change to achieve this vision?

While the motivations for embracing this approach are compelling, the pathways to achieving this vision are not always straightforward.Without careful protection of remaining natural assets, from remnant patches of vegetation to single trees, vegetation in cities can easily suffer “death by 1,000 cuts”. Planning reform is required to move away from offsetting and remove obstacles to innovation in onsite biodiversity protection and enhancement.

In addition, real or perceived conflicts between biodiversity and other socio-ecological concerns, such as bushfire and safety, must be carefully managed. Industry-based schemes such as the Green Building Council of Australia’s Green Star system could add incentive for developers through BSUD certification.

Importantly, while BSUD is generating much interest, working examples are urgently required to build an evidence base for the benefits of this new approach.

Georgia Garrard, Senior Research Fellow, Interdisciplinary Conservation Science Research Group, RMIT University; Nicholas Williams, Associate Professor in Urban Ecology and Urban Horticulture, University of Melbourne, and Sarah Bekessy, Professor, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.