|

| Vancouver (Shutterstock) |

Who can we learn from? In July, the lead author returned to three cities comparable to Melbourne that she visited in 2015 – Vancouver, Portland and Toronto – to re-interview key housing actors and review investment and policy changes over the past three years. All have big housing affordability problems, caused by a strong economy and 30 years of largely unregulated speculative housing. A lack of federal government involvement has exacerbated these problems.

But these four cities have recently developed very different approaches to housing systems planning, with increasingly divergent results. Toronto has gone backwards. Vancouver and Portland, though, are reaping the rewards of good metropolitan policy, from which we have drawn ten lessons for Melbourne.

Before we discuss these, let’s take stock of the affordable housing challenge in Melbourne.

Who needs affordable housing, and how much of it?

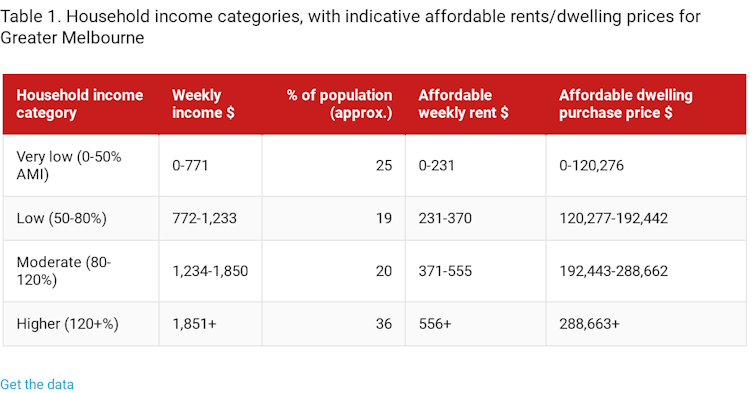

The Victorian state government has recently defined affordable housing incomes and price points for both Greater Melbourne and regional Victoria for households on very low (0-50% of median income), low (50-80%) and moderate (80-120%) incomes. It has enshrined “affordable housing” as an explicit aim in the Planning and Environment Act. Better protection for renters has also been developed.

These are great steps, but we need to go further in the next term of government.

The Australian government estimated that 142,685 lower-income renter households in Victoria were in housing stress in 2015-16. Over 30% and in many cases over 50% of their income was going to rent or mortgage payments.

Our research team at Transforming Housing has more recently calculated a deficit of 164,000 affordable housing dwellings. Over 90% of the deficit is in Greater Melbourne.

A simplified version of the price points necessary for households to avoid housing stress (one that leaves out household size and additional costs and risks of poorly located housing on the city fringe) looks like this:

Affordable home ownership bears no resemblance to the current market in which the median unit price is well over $700,000. Median rents are affordable to many moderate-income households, at about $420 a week. Whether such housing is available, with a vacancy rate of less than 1%, is another issue, particularly for very low-income households.

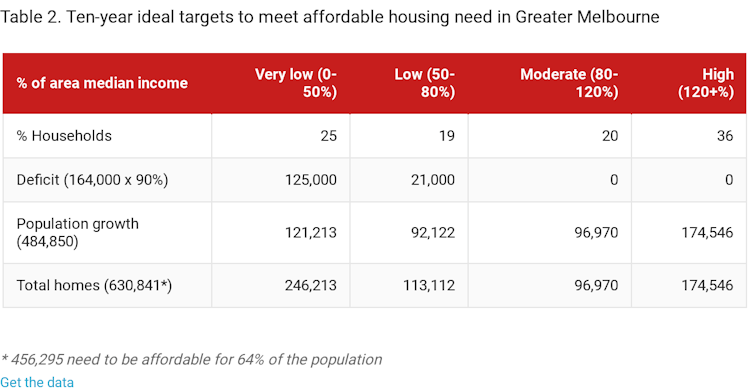

The Victorian government has a metropolitan planning strategy that states the need for 1.6 million new dwellings between 2017 and 2050. That’s almost 50,000 new homes a year. Using the new definitions, we can calculate ideal ten-year new housing supply targets to meet the needs of all residents of Greater Melbourne.

The biggest problem is not overall supply. In the six months from February to July 2018, there were 28,602 dwelling unit approvals in Greater Melbourne. At that rate there would be 572,040 new units by 2028, which is more than the total need projected by Plan Melbourne.

The problem is that the price points of these dwellings are beyond the means of 64% of households – 456,295 would need to be affordable, appropriately sized and located to meet most people’s needs. All too many will be bought as investments and remain vacant.

Plan Melbourne doesn’t provide targets for affordability, size or location. This is left to six sub-regions, each with four to eight local governments, which have not produced these reports in the 18 months since the plan was released.

Affordable housing targets that exist in state documents are woefully inadequate. Homes for Victorians has an overall target of 4,700 new or renovated social housing units over the five-year period 2017-22.

An inclusionary zoning pilot on government-owned land might yield “as many as” 100 social housing units in five years. Public housing renewal on nine sites is expected to yield at least a 10% uplift, or 110 extra social housing units, in return for sale of government land to private developers. This is certainly not maximizing social benefit.

What can we learn from Vancouver and Portland?

Although Vancouver has huge housing affordability issues, it has been able to scale up housing delivery for very low-income households – about 15 times as much social and affordable housing as Melbourne over the past three years. Both Vancouver and Portland have ambitious private sector build-to-rent programs, with thousands of new affordable rental dwellings near transport lines.

Both cities have influenced senior governments. Canada is investing C$40 billion (A$42.6b) over the next ten years in its National Housing Strategy.

In contrast, Toronto has had a net loss of hundreds of units of social housing. This is due to disastrous lack of leadership at local and state (provincial) levels.

Our new report highlights 10 lessons for the Victorian government:

- Establish a clear and shared definition of “affordable housing”. Enabling its provision should be stated as a goal of planning. This has been done.

- Calculate housing need. We have up-to-date calculations, broken down by singles, couples and other households, as well as income groups, in this report

- Set housing targets. Ideally, you would want a target of 456,295 new units affordable to households on very low, low and moderate incomes. Both Infrastructure Victoria and the Everybody’s Home campaign have suggested a more attainable ten-year target: 30,000 affordable homes for very low and low-income people over the next decade. This would allow systems and partnerships between state and local government, investors and non-profit and private housing developers to begin to scale up to meet need.

- Set local targets. The state government, which is responsible for metropolitan planning, should be setting local government housing targets, based on infrastructure capacity, and then helping to meet these targets (and improve infrastructure in areas where homes increase). We have developed a simple tool we call HART: Housing Access Rating Tool. It scores every land parcel in Greater Melbourne according to access to services: public transport, schools, bulk-billing health centres, etc.

- Identify available sites. We have mapped over 250 government-owned sites, not including public housing estates, that could accommodate well over 30,000 well-located affordable homes, with a goal of at least 40% available to very low-income households. Aside from leasing government land for a peppercorn rent, which could cut construction costs by up to 30%, a number of other mechanisms could quickly release affordable housing. Launch Housing, the state government and Maribyrnong council recently developed 57 units of modular housing on vacant government land, linked to services for homeless people. The City of Vancouver and the British Columbia provincial government recently scaled up a similar pilot project to 600 dwellings built over six months.

- Create more market rental housing. Vancouver has enabled over 7,000 well-located moderately affordable private rental apartments near transport lines in the past five years, using revenue-neutral mechanisms. Portland developers have almost entirely moved from speculative condominium development to more affordable build-to-rent in recent years.

- Mandate inclusionary zoning. This approach, presently being piloted, could be scaled up to cover all well-located new developments. Portland recently introduced mandatory provision of 20% of new housing developments affordable to low-income households or 10% to very low-income households. If applied in Melbourne, this measure alone could meet the 30,000 target (but not the current 164,000 deficit or 456,295 projected need).

- Dampen speculation at the high end of the market. This would help deal with the oversupply of luxury housing. Taxes on luxury homes, vacant properties and foreign ownership could help fund affordable housing.

- Have one agency to drive these changes. The impact of an agency like the Vancouver Affordable Housing Agency is perhaps the most important lesson. The Victorian government has over a dozen departments and agencies engaged in some aspect of affordable housing delivery. We suggest repurposing the Victorian Planning Authority with an explicit mandate to develop and deliver housing affordability, size diversity and locational targets set by the next state government.

- A systems approach is essential to build capacity. It will take time, coordination and political will for local governments to meet targets, non-profit housing providers to scale up delivery and management of social housing, private developers and investors to take advantage of affordability opportunities, and state government to plan for affordable housing. Eradicating homelessness and delivering affordable housing for all Victorians is possible. But it needs a systems approach.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.